Ground collision and evacuation

Jazz Aviation LP

DHC-8-311, C-FJXZ

and

Menzies Aviation

Rampstar Fuel Tanker

Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 10 May 2019, at 0133 Eastern Daylight Time, during the hours of darkness, a de Havilland DHC-8-311 aircraft (registration C-FJXZ, serial number 264), operated by Jazz Aviation LP as flight JZA8615, and a Rampstar fuel tanker, operated by Menzies Aviation, collided on the apron at the Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario. The aircraft was carrying 52 passengers, 3 of whom were infants. In addition, there were 3 crew members and 1 person occupying the flight deck observer seat. The passengers and crew evacuated the aircraft and were guided to the terminal building by the first responders, who included airport officials and aircraft rescue and fire-fighting service personnel. There was no fire and no fuel spillage. The emergency locator transmitter did not activate following the collision. There were 15 minor injuries reported, including 1 infant and 1 crew member.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the occurrence

On 09 May 2019, at 2303,Footnote 1 a de Havilland DHC-8-311 aircraft (registration C-FJXZ, serial number 264), operated by Jazz Aviation LP (Jazz) as flight JZA8615, departed the Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport (CYYZ), Ontario, on a scheduled instrument flight rules flight to Sudbury Airport (CYSB), Ontario. The aircraft was carrying 52 passengers, 3 of whom were infants; 3 crew members; and 1 person (a flight attendant from another airline) occupying the flight deck observer seat. The flight was expected to last 48 minutes. The weather conditions at CYSB were below minimums for landing. Following 20 minutes in a holding pattern over CYSB, the flight crew returned to CYYZ.

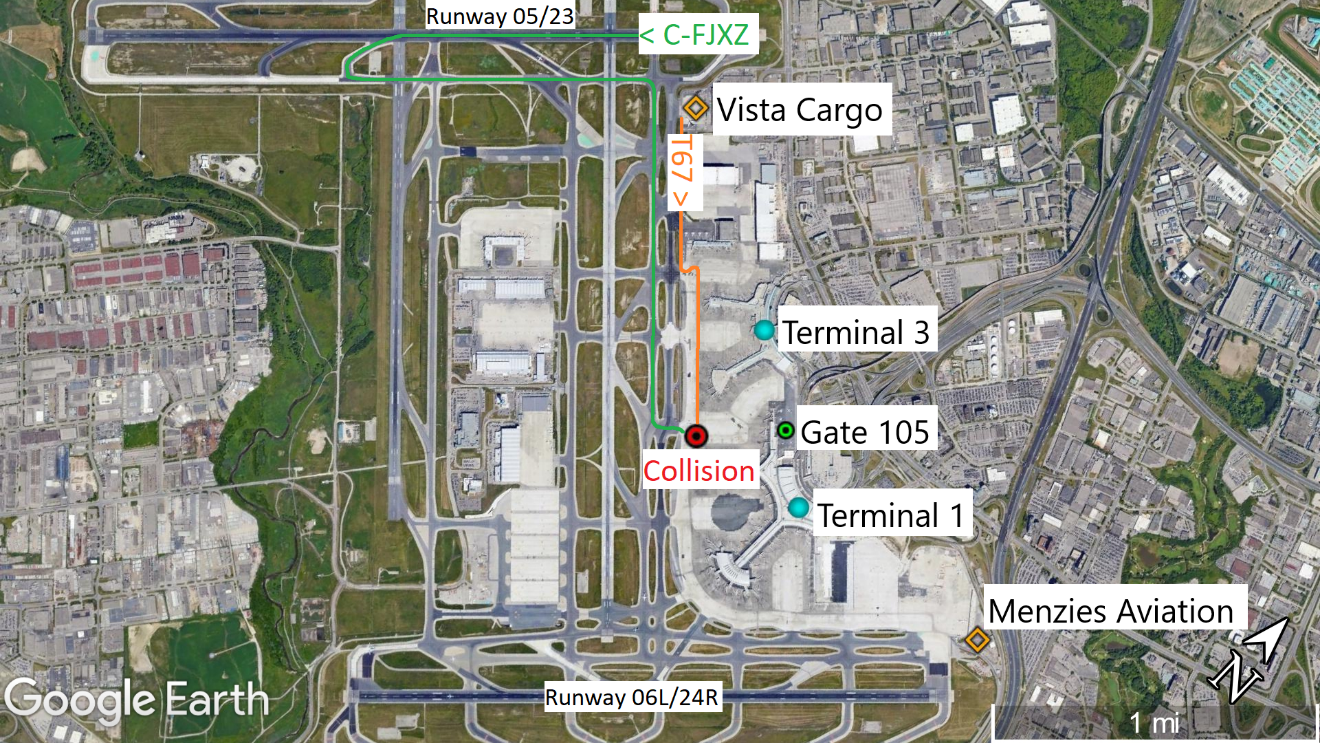

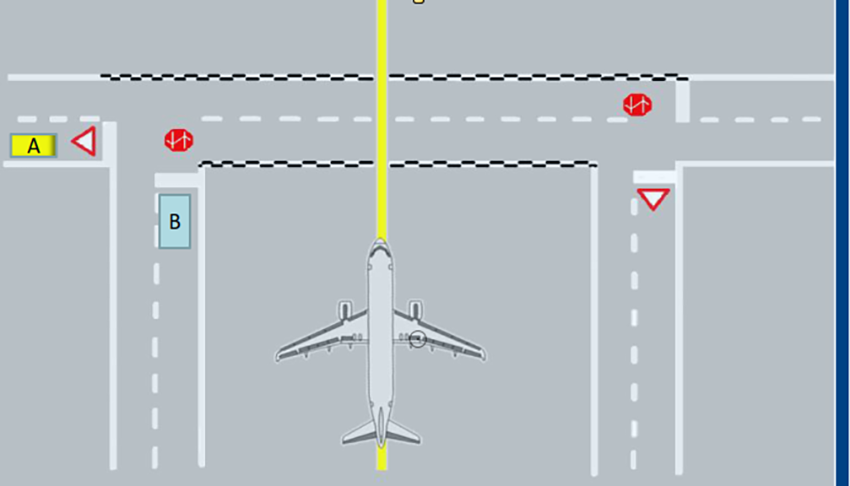

At 0126 on 10 May 2019, the aircraft landed on Runway 23. After exiting Runway 23 onto Taxiway H2, the flight crew featheredFootnote 2 the left-hand propeller in accordance with their after-landing check.Footnote 3 The flight crew received taxi instructions and continued via taxiways H, B, and AK (Figure 1). While on Taxiway AK, the first officer (FO) contacted apron control and received instructions to follow Lane 6 to Gate 105 at Terminal 1. This occurred approximately 10 seconds before the collision.

At 0127, the driver of a Rampstar fuel tanker operated by Menzies Aviation had been fuelling an aircraft on the Vista Cargo ramp, which was located near the northeast corner of the airport, just south of the threshold of Runway 23. Having finished his shift, the driver was returning to the Menzies Aviation facility, located to the north of the threshold of Runway 24R, at the eastern edge of the airport (Figure 1).

According to the Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA) Airport Traffic Directives, the inner vehicle corridors shall be used to transit between gates while the outer perimeter corridors shall be used to transition between terminals, which minimizes traffic around the terminals.Footnote 4 However, because the pavement appeared to be uneven and there appeared to be potentially hazardous conditions on the outer perimeter corridor, the driver of the fuel truck used the inner vehicle corridor.

At 0129, the fuel tanker entered the inner vehicle corridor at Terminal 3 and proceeded southbound on the apron. Due to the weather conditions and the fact that the driver’s clothing was wet from working in the rain, there was condensation on the inside of the window glass of the driver’s cab. The driver opened the left side window in an attempt to mitigate the effects of the condensation.

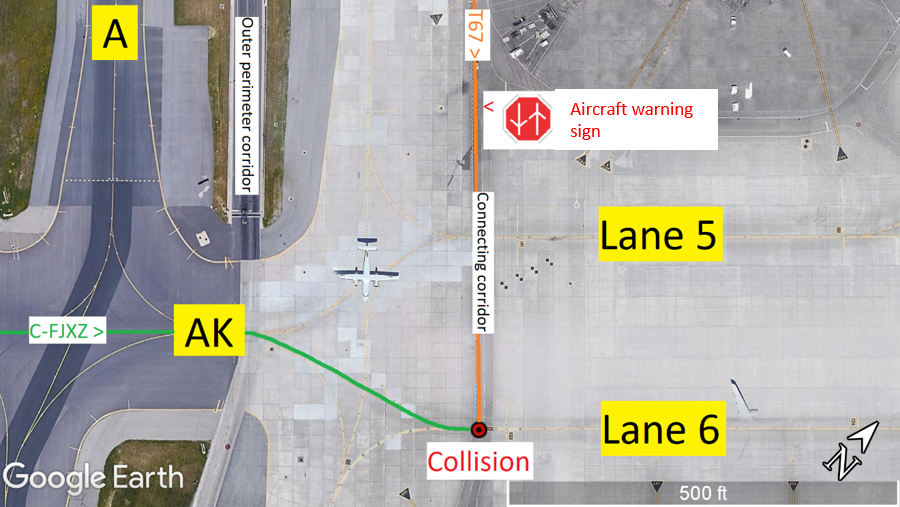

At 0133:33, the aircraft entered the Terminal 1 apron at Taxiway AK, making a slight right turn to follow Lane 6 to its assigned gate. Immediately before crossing the connecting corridor, the flight crew made a slight left turn to follow the Lane 6 centreline (Figure 2).

At 0133:36, the fuel tanker crossed an aircraft warning sign painted on the apron surface just before the connecting corridor (Figure 2). These signs serve as a reminder for drivers that they are about to cross an aircraft taxilane, and that they are to exercise vigilance. Drivers are not required to slow or stop in the absence of aircraft traffic. The fuel tanker did not slow or stop near the aircraft warning sign, and continued southbound at a speed of approximately 40 km/h, which is the speed limit.

A number of passengers seated on the left side of the aircraft saw the fuel tanker in the moments before the collision and were aware that a collision was about to occur.

At 0133:48, the aircraft was taxiing at a speed of approximately 18.5 km/h (10 knots) along the centreline of Lane 6 and the fuel tanker was travelling at a speed of approximately 40 km/h (21.5 knots) when the aircraft and fuel tanker collided. The collision occurred at the intersection of the southbound lane of the connecting corridor and the Lane 6 centreline.

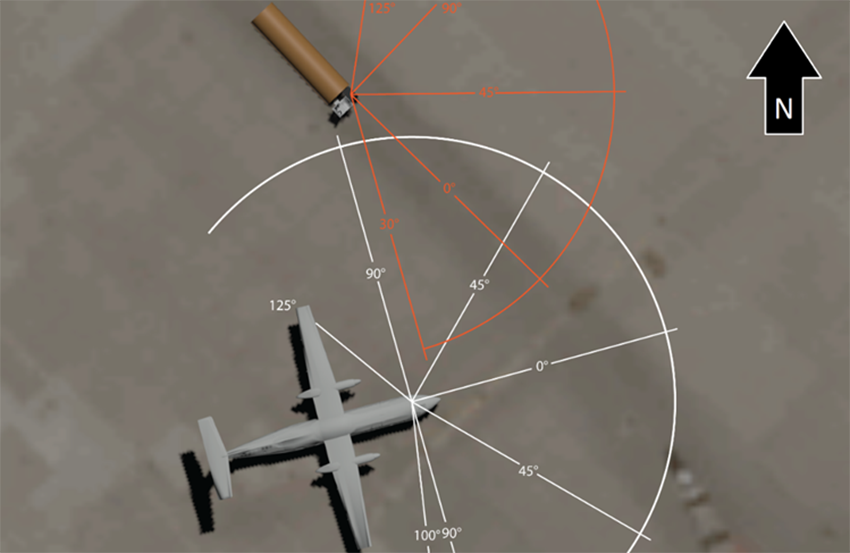

As a result of the collision, the aircraft spun approximately 120° to the right before the rear of the aircraft collided with the back of the fuel tanker and rebounded slightly. The aircraft came to a stop facing approximately 100° to the right of the original direction of travel.

Following the collision, the flight attendant commanded the passengers to remain seated. Despite this command, some passengers unfastened their seat belts and stood up.

Given the orientation of the 2 vehicles after the collision sequence (Figure 3), neither the flight crew nor the flight attendant could see the fuel tanker, nor could the driver of the fuel tanker see the aircraft.

At 0134:20, while the propellers were still turning, the passenger who had been seated in seat 9F climbed over the back of the seat, opened the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2), threw it outside, and jumped from the exit, followed by a 2nd passenger.

Simultaneously, another passenger opened the left-hand rear emergency window exit (exit L2), but closed it immediately as the fuel tanker was nearby, and the smell of exhaust and noise of the engines entered the cabin.

By 0134:38, the propellers came to a stop after the flight crew had shut down the engines. The FO made a radio call to apron control stating that the aircraft had been hit by a truck and requesting emergency equipment. The captain called the flight attendant via the interphone system and instructed her to begin a rapid deplanement.Footnote 5

At 0135:02, due in part to increasing pressure from the passengers, including verbal threats from one of them, the flight attendant opened the main door (exit L1) slowly, because she was unsure whether there was an obstruction or hazard below the opening. Once she began to open the door, she smelled fuel and decided to proceed with an evacuation rather than a rapid deplanement. She began shouting commands to “EVACUATE, EVACUATE, EVACUATE.”

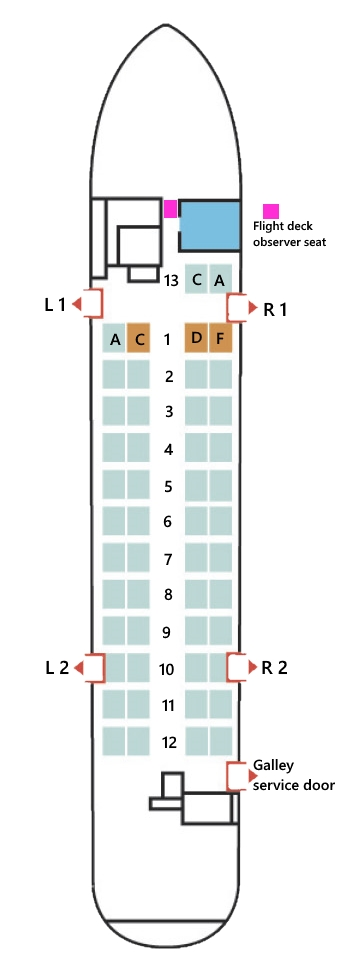

The majority of the passengers exited the cabin via the main door exit L1. Only 4 passengers, including 1 who was travelling with an infant, opted to exit via the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2).

At 0137:26, the final occupant (the captain) exited the aircraft.

1.2 Injuries to persons

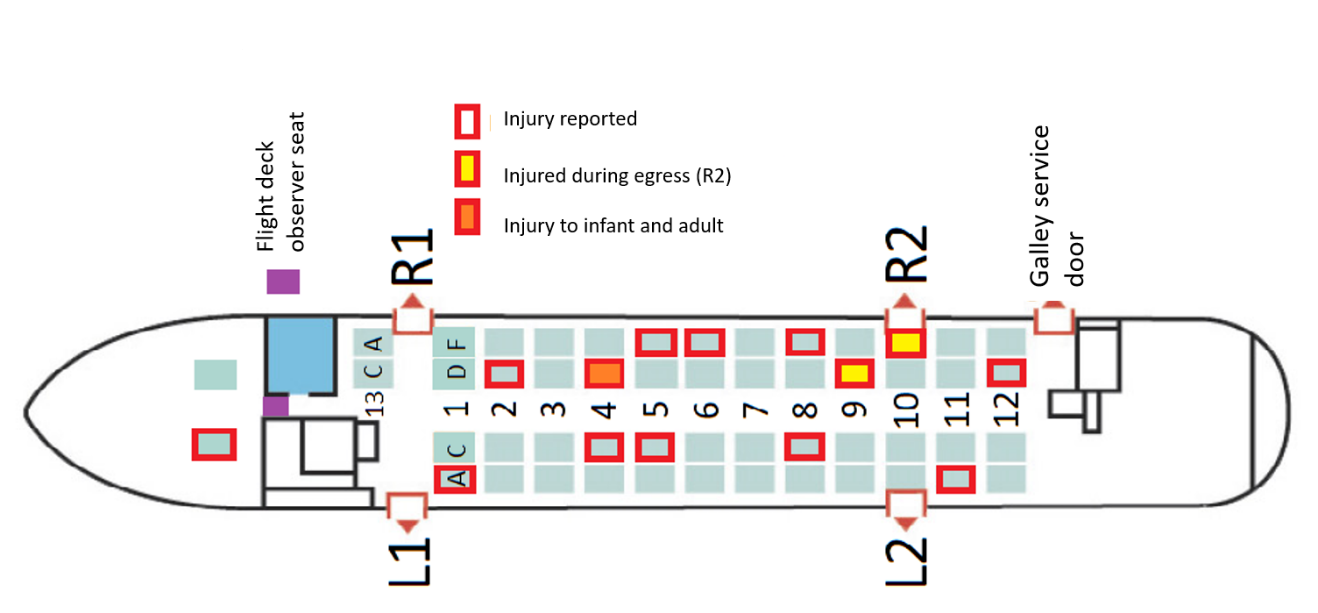

Injuries to 1 crew member and 14 passengers were reported during the triage following the occurrence (Table 1).

| Crew | Passengers with assigned seats | Flight deck observer seat occupant | Lap-held infants | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3 | 49 | 1 | 3 | 56 |

| Reported injuries | 1 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

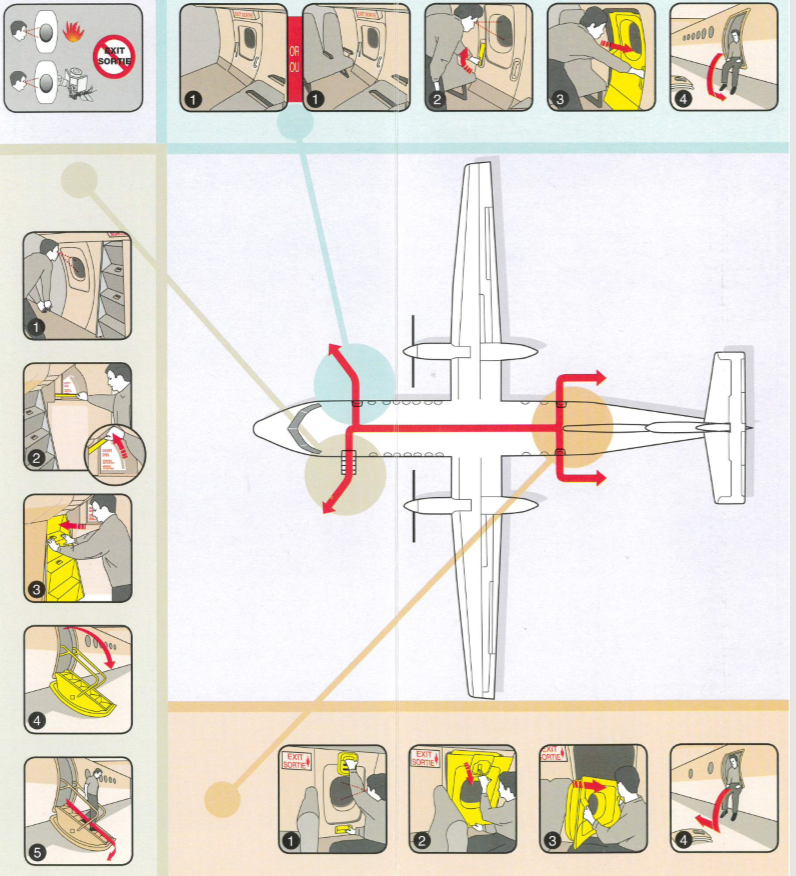

Of these injuries, 2 occurred while evacuating, both as a result of jumping from the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2) (Figure 4).

Shortly before the collision, a passenger seated within view of the flight attendant took off her seat belt. The flight attendant directed her to refasten her seat belt and remain seated. The passenger did not comply with the flight attendant’s direction, and was thrown to the floor by the impact.

The captain received a fractured rib due to direct impact forces, as he was seated adjacent to the point of impact; there was some deformation to the interior of the aircraft in the vicinity of his left armrest and the circuit breaker panel located aft of the armrest area. The captain was able to exit the aircraft without assistance once the passengers had deplaned.

Due to the direction of both the initial impact and the secondary impact with the back of the fuel tanker, occupants of the aircraft were exposed to lateral impact forces, which led to back, shoulder, hip, head, and neck injuries. These types of injuries can be caused by flailing while being restrained only by a lap belt.

Of the 3 infants on board the aircraft, 2 were being held on the lap of a family member, and 1 was being held in a soft-structured baby carrier attached to her mother. Both unrestrained infants were ejected from the arms of the adults carrying them. One infant hit the seat in front of her before falling into the aisle, and received significant bruising. The other infant collided with the neighbouring passenger, but was not injured. The infant who was held in the baby carrier was not injured; however, the infant’s mother received injuries to her back and ribcage due to twisting forces resulting from the momentum of the infant strapped into the carrier.

The driver of the fuel tanker did not report any injuries following the collision.

1.3 Damage to aircraft

The aircraft was damaged beyond repair, and has been withdrawn from service.

1.4 Other damage

The fuel tanker was substantially damaged. It was repaired and returned to service.

1.5 Personnel information

The 3 crew members were certified and qualified for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

1.5.1 Captain

The occurrence captain had over 12 000 flight hours on the DHC-8, with over 12 years as captain on the aircraft. He had woken up at 0800 on 09 May 2019 and driven for approximately 3 hours from his home in Québec, Quebec, to Montréal/Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport (CYUL), where his duty day began at 1300. He had been off duty for more than 4 days previous to the day the occurrence flight departed.

1.5.2 First officer

The occurrence FO had over 2700 flight hours, with 1280 flight hours on the DHC-8. He had reported for duty at 1300 in CYUL, after being off duty for more than 5 days previous to the day the occurrence flight departed.

1.5.3 Flight attendant

The flight attendant had been with Jazz since April 2015 and had completed the required annual trainingFootnote 6 in March 2019, which was 2 months before the occurrence. The flight attendant had been off duty on 8 May 2019, the day before the occurrence flight departed.

1.5.4 Driver of the fuel tanker

The driver had begun his employment at Menzies Aviation in November 2018, after receiving his Driver Airside – Airside Vehicle Operator PermitFootnote 7 in October 2018. According to Menzies’ training records, he received training on the operation of hydrant dispenser vehiclesFootnote 8 and began to operate these trucks on the apron area in December 2018.

In March 2019, he began training to drive the tanker trucks of various sizes, including the type he was driving on the night of the occurrence, and was authorized to operate them by himself on 13 April 2019. There were no training deficiencies noted in his training file.

The driver had been working his 3rd consecutive afternoon shift. There was no information to indicate that he had not been adequately rested before his shift on 09 May 2019.

1.6 Aircraft and vehicle information

1.6.1 The aircraft

1.6.1.1 General

| Manufacturer | Boeing of Canada Ltd. de Havilland Division |

|---|---|

| Type, model and registration | DHC-8-311, C-FJXZ |

| Year of manufacture | 1991 |

| Serial number | 264 |

| Certificate of airworthiness/flight permit issue date | 19 March 1991 |

| Total airframe time | 64 039 |

| Engine type (number of engines) | PW123A (2) |

| Propeller/Rotor type (number of propellers) | Hamilton Standard Model 14SF-15 (2) |

| Maximum allowable takeoff weight | 18 643 kg |

| Recommended fuel type(s) | Jet A, Jet A-1, Jet B |

| Fuel type used | Jet A |

Records indicate that the aircraft was certified, equipped, and maintained in accordance with existing regulations and approved procedures. Before the collision, all exterior lights were illuminated as required.

1.6.1.2 Emergency exits

The aircraft has 4 exits designated as emergency exits on the passenger briefing card, with 1 of those being the main exit door, which is designated L1 (Figure 5). Because the airstairs are incorporated into this door, the door does not contain a window or viewing port. A 2nd front emergency exit door (R1) is located across from the main door (L1). It does contain a window, and the sill height is the same as that of the main entry door (flush with the cabin floor, approximately 42 inches above ground level).

The rear emergency window exits, designated L2 and R2, are smaller than exits L1 and R1 and have a sill height of approximately 23 inches above the cabin floor and approximately 65 inches above the ground. A galley service door located behind row 12 on the right-hand side of the aircraft is not considered an emergency exit, but could be used as a means of egress as a last resort.Footnote 10

1.6.2 Fuel tanker

1.6.2.1 General

The fuel tanker was a Rampstar RFRD Series fuel tanker (Figure 6), (Model RF10-RD-2-1C), manufactured in 2014 by Engine & Accessory Manufacturing Inc. The company. based in Miami, Florida, United States, specializes in off-highway custom-built chassis for aviation refuelling and ground support equipment. The fuel tanker has a gross vehicle weight rating of 49 895 kg (110 000 pounds).

This design incorporates a rear-mounted engine, a single rear drive-axle with 2 wheels per side, and tandem front steering axles. The chassis are shipped to a truck body builder to have the fuelling equipment installed and tested. The occurrence vehicle had a tank with a capacity of 37 854 L (10 000 U.S. gallons) mounted to its chassis, with a fuelling station and controls at the rear of the truck, as well as a built-in ladder to access the top of the tank, and a front elevating service platform containing an additional fuelling station.

The low-slung design of the RFRD Series tanker allows for more clearance between the top of the tanker truck and the underside of the wings of the large aircraft they are designed to refuel. This is a common configuration for airport refuelling tankers.

Records indicate that the fuel tanker was inspected and maintained in accordance with the Menzies Aviation maintenance schedule. At the time of the collision, all appropriate exterior lights were operable and switched on.

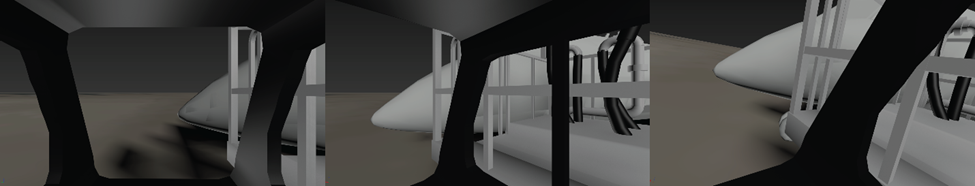

1.6.2.2 Driver’s cab

The driver’s cab, which contains a single seat, is located at the front left side of the fuel tanker, occupying approximately ⅓ of the frontal area of the truck. The windshield is a single piece of flat glass with a windshield wiper mounted above. The left side window is part of the door, as in typical road vehicles, and can be opened and closed by the driver. There is a split window to the right of the driver’s seat, between the driver and the service platform: it can be operated to slide open approximately halfway, with the rear portion being the sliding pane. There is a fixed panel of glass in the ceiling of the driver’s cab.

The height of the driver’s seat is adjustable and incorporates an air suspension to compensate for the lack of suspension or shock-absorption built into the chassis. When the truck is lightly loaded, drivers report that small bumps in the road can be magnified by the seat’s suspension, and the driver can be jolted up and down.

1.6.2.3 Defog controls

The fuel tanker was equipped with an electrically heated defog system, with nozzles that could be positioned by the driver to maximize their effectiveness by directing the airflow to the windshield. Also, the left-hand window could be opened manually, and the rear pane of the right side window could slide forward to admit outside air.

Following the collision, the defog controls in the fuel tanker were found to be set in such a way that they were not operating at their full potential, the left-hand window was fully open, and the right-hand window was closed.

1.6.2.4 Front elevating service platform

The front elevating service platform is located on the front right side of the tanker, occupying approximately ⅔ of the frontal area of the truck. The platform is surrounded by safety rails, which provide fall protection for the operator, as well as a structure on which to mount the hoses and nozzles required to refuel aircraft (Figure 7).

The operator accesses the platform from the front through a gate that is closed during fuelling operations. While fuelling, the operator occupies the platform and raises it as needed to access the fuel port(s) of the aircraft. When fuelling is complete, the platform must be stowed in its lowest position so that a micro-switch can close, allowing the truck to be driven.

There is a side-view mirror attached to the right side of the platform: the mirror occupies one of the few areas where a sightline to the right is available to the operator. The lower horizontal bars of the guardrail, located immediately adjacent to the right-hand window in the driver’s cab, directly obstruct the field of view; they are located at a position where they block a direct line of sight from the eye height of many drivers (Figure 8).

Truck body builders who install the fuel tanks and fuelling systems onto these chassis must construct the fuelling equipment and structures according to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) specifications. Footnote 11 The structures and equipment used, and their placement, are known to vary depending on the truck body builder, while remaining in compliance with the specifications.

1.7 Meteorological information

The CYYZ aerodrome routine meteorological report (METAR) issued 9 minutes before the occurrence indicated visibility as 2.5 statute miles in light rain and mist, with clouds overcast at 200 feet above ground level . The wind was from 150 °true at 10 knots, gusting to 16 knots. The temperature and dew point were both 15 °C, indicating that the relative humidity was at or very near 100%. It had been raining steadily for at least 1 hour before the collision, and the taxiway and apron surfaces were wet and reflective in appearance.

1.8 Aids to navigation

Not applicable.

1.9 Communications

1.9.1 Aircraft cabin communication equipment

Communication between the cabin crew and the flight crew is achieved by use of the cabin interphone system, which has a dedicated control unit located on the flight deck, as well as at each flight attendant station.

Passenger address (PA) announcements are also made using the cabin interphone system; they can originate from either the flight deck or one of the flight attendant stations. There are 2 speakers in the cabin through which PA announcements are heard: 1 located at the front of the passenger cabin and 1 located at the rear of the cabin.

It is not unusual for the flight attendant to be unable to hear the announcements made by the captain while at the flight attendant station (the incharge, or lead flight attendant, station) located adjacent to the main door (exit L1). It can also be difficult for passengers to hear the announcements, depending on the noise level in the cabin, even though the PA volume varies automatically depending on whether or not the engines are running. During the series of flights on the day of the occurrence, the flight attendant had been relaying the captain’s communications to the passengers from her PA handset at the incharge station.

1.10 Aerodrome information

1.10.1 Greater Toronto Airports Authority

The GTAA has been the operator of CYYZ since 1996. It is responsible for the construction, maintenance, and operation of the airport facilities.

1.10.1.1 Vehicle corridors

Drivers of vehicles on the vehicle corridors and apron areas at CYYZ are not required to be in radio contact with a controlling agency. They operate based on a set of rules implemented by the GTAA in a document entitled Airport Traffic Directives.Footnote 12

The vehicle corridor system exists entirely for the use of ground vehicle operators; pilots of taxiing aircraft do not operate with reference to them. The speed limit within vehicle corridors is 40 km/h, and the Airport Traffic Directives indicate that drivers should drive at reduced speed during adverse conditions.Footnote 13

1.10.1.2 Right-of-way

The Airport Traffic Directives state that “[a]ircraft always have the right-of-way”Footnote 14 over all other traffic on the apron areas, including emergency vehicles with active lights and sirens.Footnote 15

1.10.1.3 Outer perimeter corridors

Outer perimeter corridors at CYYZ run between apron entrances along the outer edge of the apron. They are the main arteries for vehicular traffic between apron areas in the midfield and the main terminals, as well as between the main terminals.

Outer perimeter corridors are composed largely of asphalt, except for areas where they cross aircraft taxilanes. Those areas are normally concrete. Asphalt surfaces are susceptible to wear and tear due to seasonal variations in temperature as well as deformation by heavy vehicle traffic.

Following previous concerns from fuel tanker drivers about the condition of the pavement on the outer perimeter corridors, GTAA engineering performed an assessment on areas of concern and found the condition of the pavement to be within acceptable parameters.

1.10.1.4 Inner vehicle corridors

Inner vehicle corridors at CYYZ are a system of corridors painted on the apron surface. These corridors indicate where vehicular traffic may drive while operating between departure/arrival gates and main terminals. Vehicles shall enter or exit the inner vehicle corridors from the apron at any point using a 90° turn,Footnote 16 provided they yield the right-of-way to traffic already in the inner vehicle corridors.

The painted inner vehicle corridors provide clearance from arrival/departure gates while they are occupied by aircraft and the attendant activity associated with baggage transfer and refuelling. The inner vehicle corridors are intended to be used by vehicles requiring access to an arrival/departure gate. The variety and volume of vehicle traffic on the apron area, which includes the inner vehicle corridors, is significantly greater and less orderly than the traffic on the outer perimeter corridors.

The inner vehicle corridor surfaces are largely composed of concrete, which can bear much greater loads and is not as susceptible to deformation by heavy traffic.

According to the GTAA’s Airport Traffic Directives, the inner vehicle corridors shall be used to transit between gates, while the outer perimeter corridors shall be used to transit between terminals, which minimizes traffic around the terminals.Footnote 17

1.10.1.5 Connecting corridors

Connecting corridors are marked by parallel checkered white lines on both the outer perimeter corridors and the inner vehicle corridors. They indicate areas where vehicle traffic will be crossing marked aircraft taxiways or taxilanes. They allow vehicular traffic to transit between terminal areas, as well as between the inner and outer corridors. Aircraft warning markings indicate to drivers that they are about to enter a connecting corridor (Figure 9).

1.11 Flight recorders

Information from the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) was successfully downloaded at the TSB Engineering Laboratory. This information did not provide any data beyond the moment of impact, because the electrical connections to both devices were disrupted as a result of the collision.

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

1.12.1 The aircraft

The left-side cockpit area was the first point of contact on the aircraft during the collision. It sustained significant damage immediately below the left-side window of the flight deck. There was some deformation to the interior of the aircraft in the vicinity of the captain’s left armrest and the circuit breaker panel located aft of the armrest area, which extended from floor height to the armrest. Some of the systems relevant to this occurrence, which are electrically powered through this panel, include the CVR, the FDR, and the PA system.

As the aircraft rotated away from the collision, the left-side propeller (which was feathered) and the outboard flap track fairings under the wing made contact with the top of the fuel tanker. The rotating motion of the aircraft was arrested when the left rear fuselage hit the back of the fuel tanker. There was significant damage to all 4 blades of the left-side propeller, the left-side flap track fairings, and the cargo door area of the rear left fuselage.

1.12.2 The fuel tanker

The front right corner of the fuel tanker, which contains the elevating service platform, was substantially damaged during the collision. The top of the main tank was struck by the feathered left-side propeller of the aircraft; it was damaged, but not punctured. The rear of the fuel tanker was struck by the rear fuselage of the aircraft at the end of the collision sequence; it received impact damage to the rear bumper and the tank access ladder.

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There was nothing to indicate that the performance of any of the personnel involved was degraded by physiological factors.

To determine if fatigue was a factor, an analysis of the flight crew’s and the fuel truck driver’s work schedules, sleep history, and circadian rhythm timing was conducted.

At the time of the occurrence, the captain had been awake for more than 17.5 hours, and the driver of the fuel tanker had been awake for more than 18 hours. However, it could not be concluded if fatigue played a role in this occurrence.

1.14 Fire

There was no fire.

1.15 Survival aspects

During the evacuation, there was sufficient lighting, and there was no fire or smoke inside the aircraft’s passenger cabin. The livable cabin space was not compromised. Some fumes from the aircraft’s engine exhaust entered the cabin after the collision when the rear emergency window exits (exits L2 and R2) were opened and the propellers were still turning during engine shutdown.

1.15.1 Rapid deplanement versus evacuation

A rapid deplanement is intended to be used in circumstances that “call for the passengers to leave the aircraft in an expeditious manner through the main entry door, without risk of injury to the passengers, crew, or damage to the aircraft.”Footnote 18 Such circumstances can include bomb threats, large fuel spills, and smoke in the cabin.

An evacuation will be initiated when the crew recognizes a life-threatening condition or if there has been a catastrophic accident. An evacuation is executed using all available and safe emergency exits.

The flight attendant is required to wait until the engines are shut down and assess the outside for hazards before starting shouted commands and initiating an evacuation.Footnote 19

1.15.2 Evacuation of the aircraft

The flight attendant initially instructed the passengers to remain seated and calm, although some were already getting out of their seats and shouting that they needed to exit the aircraft.

With the propellers still turning, the passenger who had been seated in seat 9F climbed over the back of the seat, opened the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2), and jumped from the exit, followed by a 2nd passenger.

The window exit was not equipped with stairs or an inflatable slide, nor were either required by regulations. Instructions found on the passenger safety briefing cardFootnote 20 (Figure 10) indicate that, when using the emergency window exits, passengers should first sit on the sill of the exit, then push away from the aircraft. This technique reduces the overall height of the jump. At the same time that the 2 passengers were exiting the R2 exit, another passenger opened the left-hand rear emergency window exit (exit L2), but closed it immediately because the fuel tanker was nearby, and the smell of exhaust and noise of the engines entered the cabin.

The flight crew shut down the engines, and the propellers came to a stop. The FO made a radio call to apron control stating that the aircraft had been hit by a truck and requesting emergency equipment.

The captain called the flight attendant via the interphone and instructed her to initiate a rapid deplanement. The flight attendant answered the call, but had difficulty hearing the captain over the passengers.

During this call, the smell of fuel and/or engine exhaust reached the cockpit, which is when the captain gave the order over the PA system to evacuate. The flight attendant was unable to hear this evacuation announcement because there was no speaker directly above her position at the front of the aircraft and the passengers were making a lot of noise. There are no accounts of passengers having heard this announcement.

Before initiating the rapid deplanement, the flight attendant attempted to look outside the window adjacent to seat 1A to verify that the main door (exit L1) could be used safely to exit the aircraft. However, access to this window was blocked by the fallen passenger who remained on the floor in front of seats 1A and 1C.

Many passengers ignored the instructions from the flight attendant to remain seated and calm; some were gathering their bags from the overhead compartments, and some were escalating the panic by yelling that they needed to get out of the aircraft.

At 0135:02, due in part to increasing pressure from the passengers, including verbal threats from one of them, the flight attendant opened the main door (exit L1) slowly, because she was unsure whether there might be an obstruction or hazard below the opening. Once she began to open the door, she smelled fuel and decided to proceed with an evacuation rather than a rapid deplanement. She began shouting commands to “EVACUATE, EVACUATE, EVACUATE.”

The flight attendant then opened the right-hand front emergency exit door (exit R1) to assess its usability as an exit. After determining that the risk of injury to passengers from jumping out of the exit in darkness was too high, she stood in front of it to block access. The FO and the occupant of the flight deck observer seat exited the cockpit and stood near the incharge station located adjacent to the main door (exit L1), which is where the flight attendant is meant to stand during an evacuation.Footnote 21 This reduced the flight attendant’s ability to see down the aisle and monitor passengers beyond the first few rows of the aircraft.

The flight attendant directed the passengers with shouted commands to leave their personal belongings behind and exit through the main door (exit L1); many passengers ignored the commands to leave their belongings behind. At least 1 passenger attempted to retrieve items out of a bag. When the FO began shouting commands to “Leave everything behind. Get out,” the passengers began to comply.

The flight attendant did not command the use of other emergency exits at any time, a decision consistent with her blocking the front emergency exit door (exit R1) to reduce the risk of passenger injury and within her discretion based on the Flight Attendant Manual (FAM) guidance.Footnote 22

The majority of the passengers exited the cabin via the main door (exit L1). Only 4 passengers, including 1 who was travelling with an infant, opted to exit via the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2).

During the evacuation, some passengers were observed to be lingering outside the main door (exit L1) of the aircraft. At some point, a passenger re-entered the aircraft to retrieve personal belongings. Other passengers attempted to do the same, but were turned away by the flight attendant, with the assistance of the FO.

The last passenger exited the aircraft approximately 3 minutes and 38 seconds after the collision, and 3 minutes and 6 seconds after the 1st passenger exited via the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2). At that time, approximately 2 minutes and 31 seconds had elapsed since the flight attendant’s evacuation order, which exceeded the 90 second certification standard for emergency evacuations (see section 1.17.2 Aircraft certification).

The FO exited the aircraft behind the last passenger, after which the flight attendant conducted her final check of the cabin and also exited the aircraft. The captain, who remained in the cockpit throughout the evacuation, was the last to exit the aircraft, exiting shortly after the flight attendant.

Ramp workers who were nearby at the time of the collision began to direct passengers toward a nearby gate at Terminal 1. Shortly afterward, an aviation safety officerFootnote 23 arrived on the scene, followed by a 2nd aviation safety officer, accompanied by aircraft rescue and firefighting personnel.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP098/2019 – FDR Download

- LP142/2019 – Photogrammetric Video Analysis

1.17 Organizational and management information

1.17.1 Jazz Aviation LP

Jazz has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Chorus Aviation Inc. since 2010. The company is based at the Halifax/Stanfield International Airport (CYHZ), Nova Scotia, and has been offering regional airline service to Canada and the United States on behalf of Air Canada since 2002, when Air Canada launched the brand. Jazz has approximately 5000 employees and carries more than 10 million passengers per year. Footnote 24

1.17.1.1 Seat belt sign and passenger announcements

As required by the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), Footnote 25 the Commercial Air Services Standards, Footnote 26 and Jazz procedures, Footnote 27 the seat belt sign was illuminated throughout the taxi to the point where the collision occurred.

Jazz procedures, which are based on the CARs, instruct the cabin crew to provide the following briefings to passengers regarding seat belts after each landing:

Passenger Briefings

4.5 Arrival

4.5.1 Taxi-in

To be done once the aircraft has turned off the active runway.

[…]

• To remain seated with their seatbelts fastened and cabin baggage stowed until the aircraft has come to a complete stop at the gate and seatbelt sign has been switched off. Footnote 28

This briefing was played over the PA system in both English and French after the aircraft exited Runway 23, approximately 7 minutes before the occurrence.

1.17.1.2 Taxi-in duties

The FAM does not contain a specific section on flight attendant duties during taxi-in. The guidance that is provided states that FAs should remain in their jumpseat with their lap belt and shoulder harness fastened until the aircraft has come to a complete stop and should ensure that passengers remain seated with their seat belts fastened until the seat belt sign is extinguished. Footnote 29

The Jazz FAM contains a section titled Gate & Ramp Emergencies, which lists the following procedures to be followed in the event of an emergency while taxiing:

- Assess the situation

- Notify the Captain

- Deplane/evacuate passengers, if necessary

- Move passengers to a safe area away from the aircraft

- Complete a headcount

- Keep passengers together

- Administer first aid, if required

- Remain in the area until debriefed by the Captain Footnote 30

1.17.1.3 Evacuation procedures

During an evacuation, the flight attendant is responsible for maintaining flow control to ensure an efficient evacuation through all available exits. The FAM provides the following guidance: Footnote 31

- Do everything possible to attract or direct passengers’ attention to all usable exit(s): use shouted commands, eye contact, pointing, gesturing, flashlight, etc.

- Do not allow an exit to become over-crowded while another is available

- Maintain a continuous and balanced passenger flow to all available exits or modes of egress

- Continually assess outside and inside conditions throughout the evacuation process: exits initially assessed to be blocked or otherwise unusable can become usable and vice versa

During an unplanned emergency, such as this ground collision, the use of shouted commands or commands issued by PA are the only means by which FAs can direct the use of the rear emergency exits from their position at the front of the cabin. However, the flight attendant does have access to a portable megaphone, which is stowed near the incharge station and can be used to amplify the flight attendant’s shouted commands. This device is tested during the pre-flight checks.

The Jazz aircraft operating manual details the pilots’ responsibilities during an emergency evacuation Footnote 32 and a rapid deplanement. Footnote 33 In both cases, the captain is required to secure the aircraft (apply park brake, shut down engines and electrical power), command the evacuation, and exit via the flight deck door to provide assistance to the flight attendants.

The FO is required to exit the aircraft to assist with the evacuation or deplanement, including directing passengers to a safe area.

1.17.1.4 Baby carriers

One of the infants on board the aircraft was being held in a soft-structured baby carrier. This type of carrier is worn by an adult and keeps an infant secured to the wearer’s chest. The FAM states that these carriers must be removed from the adult wearer during taxi, takeoff, landing, or anytime the seat belt sign is illuminated. Footnote 34

1.17.2 Aircraft certification

CARs Standard 525.803 stipulates the following with respect to emergency evacuations:

525.803 Emergency Evacuation […]

(c) For aeroplanes having a seating capacity of more than 44 passengers, it must be shown that the maximum seating capacity, including the number of crew members required by the operating rules for which certification is requested, can be evacuated from the aeroplane to the ground under simulated emergency conditions within 90 seconds. Compliance with this requirement must be shown by actual demonstration using the test criteria outlined in Appendix J of this chapter unless the Minister finds that a combination of analysis and testing will provide data equivalent to that which would be obtained by actual demonstration. Footnote 35

Moreover, Appendix J of Chapter 525 of the CARs states that “[e]xits used in the demonstration shall consist of one exit from each exit pair […] At least one floor level exit shall be used.Footnote 36

1.17.3 Menzies Aviation

1.17.3.1 General

Menzies Aviation is a subsidiary of John Menzies plc, serving over 200 airports across 6 continents. Its core services include ground handling, cargo, and fuelling. Footnote 37 Menzies Aviation began operations at CYYZ in 2017, when its parent company acquired Aircraft Service International Group, which had previously provided fuelling services at CYYZ. Menzies Aviation is the primary fuelling service at CYYZ; it also provides ground handling services to a number of airlines at CYYZ.

1.18 Additional information

1.18.1 Active TSB recommendation regarding child restraint systems on commercial aircraft

There is no requirement for operators of passenger aircraft, such as the DHC-8-311, to incorporate child restraint systems for infants and children.

In an investigation into the December 2012 low-energy rejected landing and collision with terrain in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut,Footnote 38 the TSB found that infants and children who are not properly restrained are at risk of injury and death, and may cause injury or death to other passengers in the event of an accident or turbulence.

As part of that investigation, the TSB produced a short video entitled “Apparent weight of a lap-held infant,”Footnote 39 which demonstrates the forces encountered when holding an infant during a sudden deceleration.

The TSB further concluded that if new regulations on the use of child restraint systems are not implemented, then lap-held infants and young children are exposed to undue risk and are not provided with a level of safety equivalent to that of adult passengers. Therefore, the Board recommended that

The Department of Transport work with industry to develop age- and size-appropriate child restraint systems for infants and young children travelling on commercial aircraft, and mandate their use to provide an equivalent level of safety compared to adults.

TSB Recommendation A15-02

In 2017, following its investigation into the March 2015 collision with terrain in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the TSB restated Recommendation A15-02, as it found in investigation A15H0002 that an infant was injured due to the lack of appropriate child restraint. This investigation led to the following risk finding:

If new regulations on the use of child-restraint systems are not implemented, lap‑held infants and young children are exposed to undue risk and are not provided with a level of safety equivalent to that of adult passengers. Footnote 40

The TSB’s latest reassessment of Transport Canada’s (TC’s) response to Recommendation A15-02 (March 2017) stated that TC had started an in-depth regulatory examination of this issue, which included collecting data and analyses done by other civil aviation authorities and was to conclude in the fall. TC was also planning a second phase to its awareness activities, starting that summer. TC then advised that it would also participate in an upcoming International Civil Aviation Organization Cabin Safety Group meeting to work on the development of revised international guidance on child restraint systems.

The Board was encouraged that TC was taking various actions. However, at that time, the Board was unable to determine whether these actions would result in specific solutions to address the safety deficiency identified in Recommendation A15-02.

Therefore, the response to Recommendation A15-02 was assessed as Satisfactory Intent.

Jazz does allow for the use of child restraint systems provided by passengers, as long as the restraint systems carry the appropriate certifications. It is also necessary for a passenger seat to be purchased and boarding pass issued for the infant who will occupy the child restraint system. Footnote 41

1.18.2 Active TSB recommendation regarding passenger safety briefings

In 2007, following its investigation into the August 2005 overrun occurrence at CYYZ, Footnote 42 the TSB found that many passengers took their carry-on baggage with them during the emergency evacuation of the aircraft, despite the fact that FAs repeatedly provided specific instructions to leave carry-on bags behind.

The Board believes that passenger safety briefings that instruct passengers not to bring their carry-on bags with them during an emergency evacuation would complement any existing measures to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of an emergency evacuation. Therefore, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport require that passenger safety briefings include clear direction to leave all carry-on baggage behind during an evacuation.

TSB Recommendation A07-07

Since this recommendation was issued, several other TSB investigations have documented passengers taking their carry-on baggage with them during an emergency evacuation . Footnote 43

The TSB’s latest reassessment of TC’s response to Recommendation A07-07 (April 2014) indicated that TC was persuaded that Advisory Circular (AC) No. 700-012: Passenger Safety Briefings Footnote 44 was having the desired effect. TC did not categorically state that all major carriers had implemented AC 700-012 to provide passengers with the instruction to leave baggage behind in the event of an emergency. Rather, its response indicated that an adequate number of carriers were providing this safety information to their passengers.

TC appeared satisfied with these results and the ongoing willingness of operators to voluntarily include this safety information in their passenger briefings. Consequently, it planned no regulatory action that would require operators to provide this information to passengers as stated in Recommendation A07-07. The action taken to date will reduce but not substantially reduce or eliminate the safety deficiency. The response is considered Satisfactory in Part.

1.18.3 Passenger behaviour and seat belt use

As required by regulations, Footnote 45 passengers on the occurrence flight were instructed to remain seated with their seat belts fastened until the aircraft came to a complete stop at the arrival gate. At least 1 passenger on the occurrence flight removed her seat belt while the aircraft was still taxiing. This resulted in her falling to the floor during impact, receiving a minor injury, and becoming an impediment to the flight attendant, who was trying to conduct her duties.

Passenger non-compliance with instructions regarding seat belt use is a recurring issue that has been documented in 2 recent TSB investigation reports. Footnote 46 These reports highlight the importance of passengers listening to instructions from crew members regarding seat belt use and the dangers associated with not wearing seat belts.

1.18.4 Minimum cabin crew complement

In 2002, TC received a request from the Air Transport Association of Canada to consider an operating rule to give airlines the option to operate their fleet with 1 cabin crew member to every unit of 50 passenger seats (1:50), in addition to the existing regulation.

The 1:50 ratio had been in effect for many years in the European Union and the United States. In 2013, TC granted an exemption to a number of operators to operate with a 1:50 ratio.

In June 2015, the regulations were amended allowing all Subpart 705 (airline operations) operators to operate with a ratio of 1 flight attendant per 50 passenger seats in parallel with the existing regulatory requirement that requires a ratio of 1 flight attendant per 40 passengers carried.

CARs section 705.201 currently stipulates the following:

Minimum Number of Flight Attendants

705.201 (1) No air operator shall operate an aeroplane to carry passengers unless the air operator does so with the minimum number of flight attendants required on each deck.

(2) Subject to subsections (4) to (7), the minimum number of flight attendants required on each deck of an aeroplane is determined in accordance with one of the following ratios that is selected by the air operator in respect of the model of that aeroplane:

- (a) one flight attendant for each unit of 40 passengers or for each portion of such a unit; or

- (b) one flight attendant for each unit of 50 passenger seats or for each portion of such a unit.

(3) Persons referred to in paragraphs 705.27(3)(c) to (e)Footnote 47 who are admitted to the flight deck are not counted as passengers for the purposes of paragraph (2)(a).

(4) An air operator who has selected, in respect of a model of aeroplane, the ratio set out in paragraph (2)(b) shall not operate an aeroplane of that model with only one flight attendant unless

- (a) the aeroplane has a single deck and is configured for 50 or fewer passenger seats;

- (b) the aeroplane was certified under [Canadian and international regulations and standards as specified in this paragraph];

- (c) only one flight attendant was used for the emergency evacuation demonstration required for the certification of that model of aeroplane;

- (d) the air operator’s flight attendant manual indicates how normal and emergency procedures differ depending on whether the aeroplane is operated with one flight attendant or with more than one flight attendant;

- (e) the flight attendant occupies a flight attendant station that is located near a floor-level exit; and

- (f) the public address system and the crew member interphone system are operative and are capable of being used at the flight attendant station.Footnote 48

The occurrence aircraft was configured with 50 seats. During the occurrence flight, there were 52 total passengers in the cabin: 49 were occupying seats, and each of the 3 infants were being carried by a family member. There was 1 unoccupied seat in the cabin.

In addition, a flight attendant from another airline was seated in the flight deck observer seat. In accordance with the CARs, this flight attendant was not counted as a passenger for the purpose of determining the minimum number of cabin crew.Footnote 48

The occurrence flight was operated in compliance with regulations relating to minimum cabin crew complement.

1.18.5 Human factors

1.18.5.1 Expectation

While taxiing their aircraft, flight crews are expected to remain vigilant and ready to respond if aircraft, vehicles, or other obstacles pose a hazard. Aircraft are not required to stop with reference to any pavement markings that may exist on the apron area, including marked vehicle corridors.

Because the occurrence flight crew were experienced in this type of environment, they would have expected any ground vehicles to yield the right-of-way to the aircraft.

While driving on the apron, ground vehicle drivers are expected to yield to aircraft at all times. Pavement markings, such as the aircraft warning signs, indicate to drivers that they are about to cross a taxilane used by aircraft; the markings prompt drivers to visually scan the crossing before proceeding. There is no requirement to stop with reference to the aircraft warning signs unless an aircraft is observed to be proceeding across, or about to proceed across, the connecting corridor.

The collision between the fuel tanker and the aircraft occurred while the GTAA night flight restriction program was in effect. When this program is in effect, the total number of departures and arrivals at CYYZ is limited. Airside drivers and pilots familiar with CYYZ are aware of the reduction in traffic during this time. This could lead to an expectation that it would be less likely for them to encounter traffic on their respective paths.

1.18.5.2 Visual scan

Drivers and pilots operating on the ground must maintain a continuous visual scan of their surroundings, which includes elements both inside and outside the vehicle they are operating. These elements include external guidance information, such as road markings or centreline markings, and internal guidance, such as taxi charts or dashboard/flight instruments, which may contain speed information. Also included is the requirement to scan for and detect obstacles in the path of the vehicle.

For an obstacle to be detected, it first needs to be perceived (such as aircraft external lighting) and then identified (such as a moving aircraft). The conspicuity, or salience, of an obstacle will influence the driver’s ability to perceive it.

1.18.5.3 Visual clutter

A visually cluttered environment has the potential to impair operating performance. While drivers or pilots are driving or taxiing during the hours of darkness at CYYZ, and at many other large airports located in urban areas, the density of lights from the airport itself and the surrounding urban area can cause clutter in their visual field. Light sources include flashing and moving lights from vehicles and aircraft, airport runway and taxiway lighting, floodlights in the apron area, and the lights of the surrounding city. Mist and wet conditions on the pavement can exacerbate this visual clutter by reflecting some of this light.

1.18.5.4 Passenger reactions

During an emergency, passengers’ reactions may vary widely, from panic to cooperation to freezing (sometimes referred to as negative panic). A 2015 study entitled Human Behaviour in emergency situations: Comparisons between aviation and rail domains, found that passengers are more likely to present reactive and cooperative behaviors.Footnote 50 The same study demonstrated that an assertive crew facilitates the management of passengers’ reactions and leads to significantly reduced evacuation time.Footnote 51

The Jazz FAM gives 2 examples of passenger reaction types that require special attention from a flight attendant or crew member:

Negative Panic:

- Their response is to “freeze” or go into denial during stressful situations.

- This type of passenger will require extra attention in leaving or evacuating the aircraft.

Positive Panic:

- Their response is to overreact during stressful situations, resulting in false leadership scenario, where the passenger attempts to take control away from the crew member.

- The passenger must be dealt with firmly and quickly before the situation becomes out of control.Footnote 52

1.19 Useful or effective investigation techniques

Analysis of video surveillance indicates that the truck was travelling at an average speed of approximately 40 km/h during the 15 seconds before the collision; the brake lights did not illuminate during this time.

Photogrammetric analysis conducted using security camera footage and land survey information allowed investigators to evaluate the sightlines from the aircraft and the fuel tanker, in conjunction with the approach angles, during the moments leading up to the collision.

The analysis determined that, because of the location of the elevating service platform and its accessories, no part of the aircraft would have been visible to the driver until approximately 3 seconds before the collision, and then only if the driver was leaning forward and looking to the right (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

There was nothing identified that obstructed the captain’s field of view of the apron during the turn onto taxiway AK, which was approximately 30 seconds before the collision, until the moment of impact.

2.0 Analysis

Records indicate that all personnel responsible for the operation of both the de Havilland DHC-8-311 aircraft (C-FJXZ) and the Rampstar fuel tanker involved in this occurrence were certified and qualified in accordance with existing regulations and/or applicable directives. All relevant systems, including exterior lighting on both the aircraft and the fuel tanker, were found to be serviceable during the occurrence.

This analysis will focus on identifying the factors that led to the collision, including the fields of view and expectations of the pilots and fuel tanker driver. Factors affecting the efficiency of the evacuation, the carriage of infants, the minimum cabin crew complement, and adherence to airport directives will also be examined.

2.1 Fields of view

The investigation determined that the limited field of view to the right of the fuel tanker driver’s cab caused by the front elevating service platform and its structural elements, along with the condensation on the windows, resulted in the driver being unable to see the aircraft in time to avoid the collision. This limited field of view at the time of the occurrence would not have allowed the driver an opportunity to perceive the presence of the aircraft until the final 3 seconds before the collision, and only then if he had been leaning forward and looking to the right.

The weather conditions at the time of the collision would only serve to exacerbate the difficulties encountered in operating a vehicle with a poor field of view. The high humidity and rainfall resulted in mist, which also reflects light, and reduced visibility. In the case of the fuel tanker, these conditions caused condensation to form on the inside surfaces of the cab windows. The defog controls were not being used to maximum effect.

The investigation did not uncover any information to indicate that the captain, who was in control of the aircraft, had obstructions to his field of view that would have prevented him from seeing the fuel tanker following his turn onto Taxiway AK, 30 seconds before the collision.

While taxiing, the captain’s attention was focused primarily on the intended path of the aircraft to maintain the centreline of the taxilane and scan for traffic or obstacles ahead.

The captain had a clear field of view in the direction of the oncoming fuel tanker but the visibility was limited due to darkness, rain, and reflected light, and he did not see the oncoming tanker during the critical moments before the collision.

2.2 Expectations

The pilots of the occurrence aircraft and the driver of the fuel tanker all had experience operating at Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport (CYYZ). They were aware that, at the time of the occurrence, there would have been very little activity on the airport manoeuvring areas.

The driver’s and flight crew’s familiarity and previous experience operating on the apron at that time of night and the expectation that it was unlikely to encounter an aircraft or ground vehicle crossing the connecting corridor may have contributed to a lower level of vigilance.

In addition, the flight crew’s previous experience operating at CYYZ, and at other busy airports, coupled with their understanding of the rules governing right-of-way, may have led to the expectation that ground vehicles would yield to their aircraft in all situations.

If drivers and flight crews do not remain vigilant to the potential for other vehicles to cross designated apron manoeuvring areas, regardless of airport activity level or vehicle right-of-way rules, there is an increased risk of collision.

2.3 Evacuation

Following the collision, because the fuel tanker was not visible from the flight deck or from the flight attendant’s position in the cabin, both the flight crew and the flight attendant needed a few moments to assess what had occurred and decide on the best course of action regarding a rapid deplanement or evacuation. In addition, the flight crew required some time to shut down the engines and allow for the propellers to stop turning before passengers could safely exit the aircraft.

After the flight crew shut down the engines, the captain called the flight attendant via the interphone and instructed her to initiate a rapid deplanement. The flight attendant answered the call, but had difficulty hearing the captain over the noise of the passengers. At that time, the smell of fuel and/or engine exhaust reached the cockpit, and the captain gave the order over the passenger address system to evacuate.

However, nobody on the aircraft reported hearing the captain’s evacuation order, possibly due to the passenger address system being damaged by the impact, , and/or passenger noise in the cabin. Due in part to increasing pressure from the passengers, including verbal threats from one of them, the flight attendant opened the main door (exit L1) slowly. When the flight attendant smelled fuel, she decided to initiate an emergency evacuation.

The hazards that existed were all closer to the rear of the aircraft, which made the use of the front exits an appropriate choice; however, the decision to block the right-hand front emergency exit door (exit R1) because of the risk of injury to passengers increased the evacuation time.

2.3.1 Passenger behaviour

Some passengers seated along the left side of the aircraft had seen the oncoming fuel tanker and were aware that a collision was imminent. Approximately 30 seconds after impact, while the propellers were still turning, some passengers near the rear of the aircraft decided to act on their own by opening the rear emergency window exits without waiting for directions from the flight crew or flight attendant.

The passenger who opened the left-hand rear emergency window exit (exit L2) closed it immediately, as the fuel tanker was nearby. The passenger who opened the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2) threw the hatch outside and then jumped from the exit. A 2nd passenger followed. A total of 4 passengers exited through this emergency exit window.

If passengers open emergency exits before an evacuation order is given, the suitability of the exit may not be assessed and a premature evacuation could occur, increasing the risk of passengers being exposed to hazardous conditions.

When the rear emergency window exits were opened, the smell of exhaust and noise of the engines entered the cabin and may have been interpreted by the passengers as a significant risk of fire and/or explosion, which resulted in an increase in panic.

Many passengers were ignoring the flight attendant’s instructions to remain seated and calm. Some were gathering their bags or items from their bags, which were located in the overhead compartments; some were escalating the panic by yelling that they needed to get out of the aircraft. Others reboarded or attempted to reboard the aircraft during and after the evacuation. If passengers attempt to retrieve personal belongings during an evacuation, they will impede or delay passengers and crew exiting the aircraft, increasing the risk of injury or death.

2.3.2 Injuries

One passenger seated at the front of the aircraft had removed her seat belt before the collision, despite the flight attendant directing her to keep her seat belt fastened and the seat belt sign being illuminated. During impact, the passenger fell to the ground near the right-hand front emergency exit (exit R1) and received injuries as a result. This injured passenger then became an obstacle to the flight attendant, who needed to access the window beside seat 1A to assess the hazards outside the aircraft. If passengers remove their seat belts while the aircraft is in motion, or while the seat belt sign is illuminated, they put themselves and others at risk of injury.

On the DHC-8-300 series of aircraft, the correct procedure for deplaning the aircraft through the rear emergency window exits is to first sit down on the edge of the opening and then jump to the ground; this reduces the effective height of the jump. This information was available to all passengers and detailed in the passenger briefing cards located in the pocket of each seat back.

The 4 passengers who exited the right-hand rear emergency window exit (exit R2) during this occurrence jumped from the full sill height of the exit, approximately 65 inches above the pavement; 2 of them were injured as a result of this jump. If passengers do not familiarize themselves with the briefing card for the specific aircraft on which they are travelling, they may not know how to operate and correctly use an emergency exit, increasing the risk of injury.

2.4 Carriage of infants

As a result of the collision, the 2 lap-held infants became separated from the adults who were holding them and came into contact with parts of the aircraft or nearby passengers. One of the infants received significant bruising.

The infant who was held in the baby carrier was not injured; however, the adult wearing the baby carrier received injuries to her back and ribcage due to twisting forces resulting from the momentum of the child strapped into the carrier. There is no requirement for operators of passenger aircraft, such as the DHC-8-311, to incorporate child restraint systems for infants and children.

If new regulations on the use of child-restraint systems are not implemented, lap-held infants and young children will continue to be exposed to undue risk and will not be provided with a level of safety equivalent to that of adult passengers.

2.5 Minimum cabin crew complement

The occurrence flight was operating according to minimum cabin crew regulations, with the required cabin crew of 1 flight attendant for 50 passenger seats.

In this occurrence, the sole flight attendant had to coordinate the evacuation of 52 passengers (49 adults and 3 infants), initially by herself, following a sudden collision. Noise in the cabin caused by shouting passengers and unruly passenger behaviour made it difficult to communicate with anybody near the rear of the cabin.

In addition, passengers standing in the aisle and holding their personal belongings prevented the flight attendant from being able to observe and assess the suitability of the exits at the rear of the aircraft. The blocked aisle also prevented her from ensuring that the exits were being used as intended, resulting in at least 2 injuries during egress.

If flight attendants are unable to directly supervise passengers for reasons of proximity or visibility, there is a risk that unsafe action or non-compliance by passengers during emergency procedures will increase the potential for injury.

2.6 Greater Toronto Airports Authority Airport Traffic Directives

According to the Greater Toronto Airports Authority’s Airport Traffic Directives, the inner vehicle corridors shall be used to transit between gates, while the outer perimeter corridors shall be used to transition between terminals, which minimizes traffic around the terminals. However, because the pavement appeared to be uneven and there appeared to be potentially hazardous conditions on the outer perimeter corridor, the driver of the fuel truck used the inner vehicle corridor.

If vehicle operators do not follow airport traffic directives with regard to vehicle corridors, there is a higher potential for traffic conflicts, increasing the risk of ground collisions.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are conditions, acts or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

- The limited field of view to the right of the fuel tanker driver’s cab caused by the front elevating service platform and its structural elements, along with the condensation on the windows, resulted in the driver being unable to see the aircraft in time to avoid the collision.

- The captain had a clear field of view in the direction of the oncoming fuel tanker but the visibility was limited due to darkness, rain, and reflected light, and he did not see the oncoming tanker during the critical moments before the collision.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are conditions, unsafe acts or safety deficiencies that were found not to be a factor in this occurrence but could have adverse consequences in future occurrences.

- If drivers and flight crews do not remain vigilant to the potential for other vehicles to cross designated apron manoeuvring areas, regardless of airport activity level or vehicle right-of-way rules, there is an increased risk of collision.

- If passengers open emergency exits before an evacuation order is given, the suitability of the exit may not be assessed and a premature evacuation could occur, increasing the risk of passengers being exposed to hazardous conditions.

- If passengers attempt to retrieve personal belongings during an evacuation, they will impede or delay passengers and crew exiting the aircraft, increasing the risk of injury or death.

- If passengers remove their seat belts while the aircraft is in motion, or while the seat belt sign is illuminated, they put themselves and others at risk of injury.

- If passengers do not familiarize themselves with the briefing card for the specific aircraft on which they are travelling, they may not know how to operate and correctly use an emergency exit, increasing the risk of injury.

- If new regulations on the use of child-restraint systems are not implemented, lap-held infants and young children will continue to be exposed to undue risk and will not be provided with a level of safety equivalent to that of adult passengers.

- If flight attendants are unable to directly supervise passengers for reasons of proximity or visibility, there is a risk that unsafe action or non-compliance by passengers during emergency procedures will increase the potential for injury.

- If vehicle operators do not follow airport traffic directives with regard to vehicle corridors, there is a higher potential for traffic conflicts, increasing the risk of ground collisions.

3.3 Other findings

These items could enhance safety, resolve an issue of controversy, or provide a data point for future safety studies.

- One passenger seated at the front of the aircraft had removed her seat belt before the collision, despite the flight attendant directing her to keep her seat belt fastened, and the seat belt sign being illuminated.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 Greater Toronto Airports Authority

At the request of the Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA), the International Air Transport Association Footnote 53 performed an audit on Menzies Aviation and its operations at Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport (CYYZ).

Additionally, the GTAA has initiated a review of the entire Airside Vehicle Operator Permit (AVOP) program, with the input of industry partners, including observations from both new and experienced AVOP drivers as well as other airside personnel.

4.1.2 Menzies Aviation

Menzies Aviation has made a number of changes to its equipment and procedures.

To enhance safety in its fuel tanker fleet, it has added rear- and side-view cameras, which are displayed on a screen in the driver’s cab, to the right of the steering wheel. It has also purchased 2-way radios to be carried by drivers for the purpose of company communications during vehicle operations.

As a means of reducing congestion on the apron areas, Menzies Aviation is implementing a system for transmitting fuel orders to a tablet contained in each vehicle, removing the need for a driver in a pickup truck to deliver fuel slips to the fuel tankers and hydrant trucks on the apron, thus reducing airside vehicle congestion. These tablets will also provide global positioning system (GPS) tracking functionality, so the company can monitor the location and speeds of its vehicles in real time.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .